Inheriting Someone Else's Network: What to Fix, What to Leave Alone, and How Not to Destroy Your Credibility

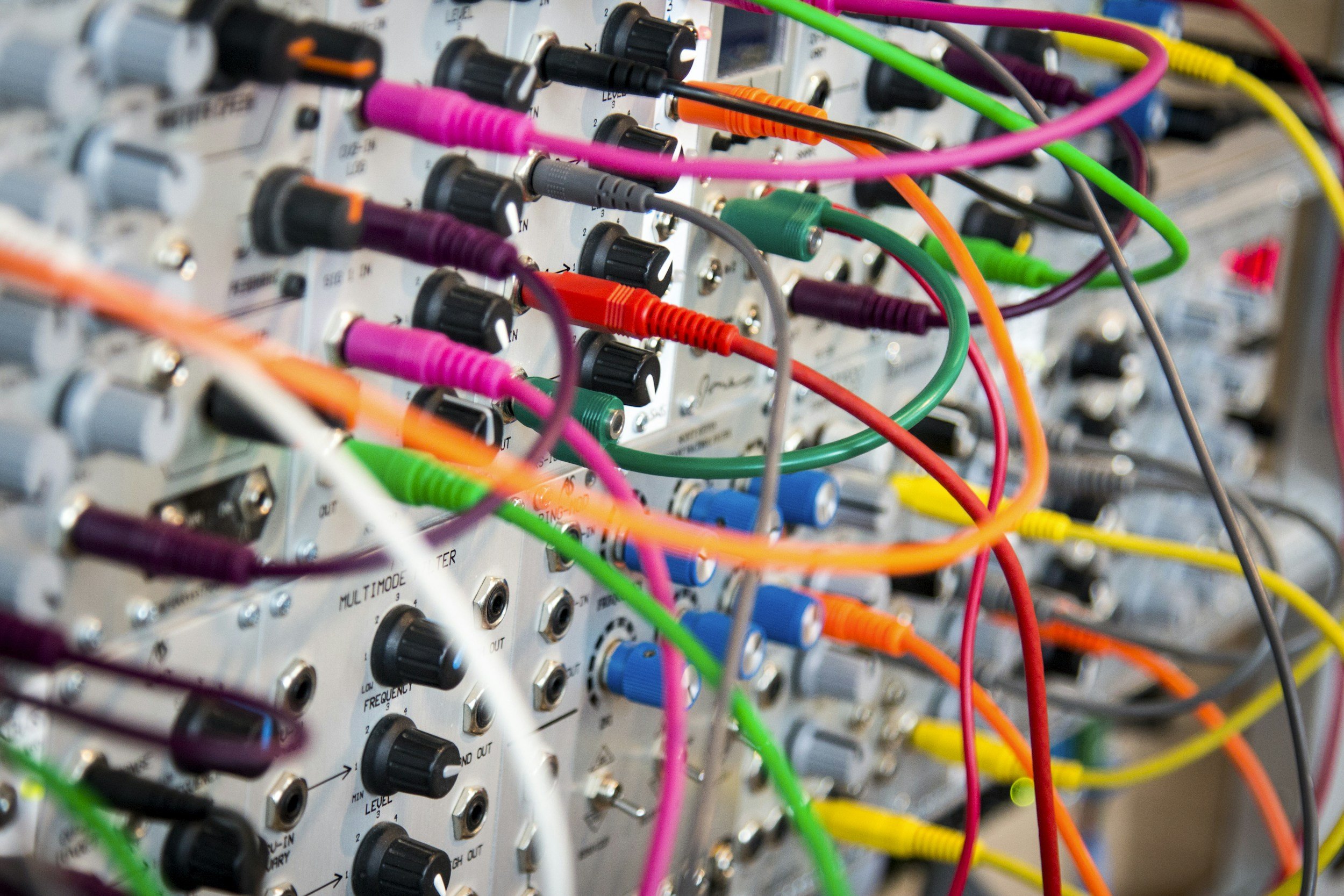

The Moment You See It

Two weeks into your new role - whether that's a promotion or a new company - you're doing the walkthrough, looking at network diagrams. reviewing configurations and understanding the architecture.

And you see it.

A design decision that makes you think "why on earth would anyone do it THIS way?"

A configuration that violates everything you know about best practices.

An architecture that's overly complex for no apparent reason.

A glaring security issue that should have been fixed years ago.

Your first instinct: "I need to fix this."

The voice of experience whispers: "Maybe wait. There might be context you're missing."

The political reality: "Change this wrong and you'll destroy your credibility before you've built any."

Welcome to one of the hardest challenges of becoming a manager or joining a new organization: inheriting someone else's network and figuring out what to fix, what to leave alone, and how to make changes without creating enemies or breaking things.

The Assessment Phase: Understanding What You Actually Inherited

Before you make any changes, you need to understand what you're actually looking at. And that takes longer than you think.

The First 30 Days: Observe and Document

Your job in the first month:

NOT changing things. Not even planning changes. Just understanding what exists and why.

What to Do:

1. Document the Current State

Actually, map what exists:

Physical and logical network topology

Key design decisions and their implications

Configuration standards (even if you disagree with them)

Known issues and workarounds

Operational pain points

Don't just skim configs. Really understand how this network operates on a day-to-day basis.

2. Talk to People Who Built It

If the previous network lead is still around (maybe they got promoted, maybe you're replacing them), talk to them and ask questions:

"Can you walk me through why you designed it this way?" "What constraints were you working with?" "What would you change if you could?" "What's the history behind [specific decision]?"

Critical: Ask these questions with genuine curiosity, not judgment. You're gathering context, not interrogating.

3. Talk to the People Who Use It

Your team, the help desk, application owners, and users.

"What works well?" "What's frustrating?" "What breaks often?" "What takes too long?"

Why This Matters:

The people living with this network daily know things you don't. Their pain points might not be what you expect.

4. Review the Last 6-12 Months of Incidents

What's actually breaking? What's causing outages? What's generating support tickets?

The Reality:

Sometimes the things that look "wrong" to you aren't actually causing problems, and sometimes the things that look "fine" are generating constant issues.

Data > assumptions.

Understanding incident patterns helps you prioritize what actually needs fixing vs. what's just aesthetically displeasing, something I explored in Managing Your Team Through a Major Outage - real problems reveal themselves through failure patterns.

The Things That Make You Cringe (But Might Be Right)

Here's what I've learned:

About 40% of the things that initially made me think "this is wrong" turned out to have good reasons behind them once I understood the context.

Example 1: The "Overcomplicated" Routing

What I Saw: Unnecessarily complex OSPF design with multiple areas when a simple single-area design would work.

My Initial Reaction: "This is over-engineered. We should simplify."

The Context I Learned: Three years ago, the company planned to expand to 20+ sites. The design was built for that scale. The expansion got cancelled, but the architecture remained. Now we're down to 8 sites, but the design isn't actually causing problems - it's just more complex than current needs require.

The Decision: Leave it. It works, and the complexity isn't hurting us. Redesigning would be high-risk for minimal benefit.

Example 2: The "Non-Standard" Configuration

What I Saw: Custom scripts for configuration backup instead of using standard network management platforms.

My Initial Reaction: "Why aren't we using [standard tool]? This is reinventing the wheel."

The Context I Learned: They tried three different commercial platforms over two years. All had issues with our specific vendor mix and multi-tenant environment. The custom scripts actually work more reliably and do exactly what we need.

The Decision: Leave it. "Industry standard" doesn't mean "right for every environment."

Example 3: The "Security Issue"

What I Saw: Legacy equipment running old firmware with known vulnerabilities.

My Initial Reaction: "This is a security risk. We need to upgrade immediately."

The Context I Learned: The equipment is isolated on a management network with no external access. It's scheduled for replacement in 4 months. Upgrading the firmware now risks breaking functionality we need for that 4-month window, and the security risk is minimal given the isolation.

The Decision: Leave it. Don't create risk by fixing a theoretical problem when a real replacement is imminent.

The Lesson: "This looks wrong" doesn't always mean "this is wrong." Seek to understand before you judge.

What Actually Needs Fixing vs. What's Just Different

Here's the framework I'm using to separate real problems from personal preferences:

Tier 1: Fix Now (Actual Problems)

Active Security Risks:

Externally exposed systems with known vulnerabilities

Default passwords or weak authentication

Missing critical security patches on internet-facing infrastructure

Obvious compliance violations with regulatory impact

Reliability Issues Causing Regular Outages:

Single points of failure for critical services

Equipment at end-of-life that's failing regularly

Configuration errors are causing repeated incidents

Capacity constraints leading to performance degradation

Operational Blockers:

Missing monitoring/alerting for critical systems

Lack of documentation is causing extended troubleshooting

Processes so broken they're creating regular crises

Financial Waste:

Paying for services/circuits no longer needed

Severe over-provisioning consuming budget unnecessarily

Licensing for tools that aren't being used

Criteria: These cause active harm. Business impact is measurable. Risk of NOT fixing exceeds risk of fixing.

Tier 2: Fix Soon (Important But Not Urgent)

Aging Infrastructure:

Equipment approaching end-of-life but not yet failing

Systems that work but are becoming unsupportable

Technology debt that will become a crisis if not addressed

Scalability Limitations:

Architecture that will hit limits as business grows

Capacity that's adequate now but won't be in 6-12 months

Designs that block planned business initiatives

Efficiency Improvements:

Manual processes that could be automated

Redundant systems that could be consolidated

Tools that could improve team productivity

Technical Debt:

Workarounds that should become permanent solutions

Missing documentation for complex systems

Configuration drift that needs standardization

Criteria: These will become Tier 1 problems if left unaddressed. You have time to fix them properly, but they're on a timer.

Tier 3: Fix When Convenient (Nice-to-Have)

Architectural Preferences:

Designs that work but aren't how you'd architect it

Standards that differ from your preferred approach

Complexity that's higher than necessary, but not causing issues

Cosmetic Issues:

Inconsistent naming conventions (that everyone understands)

Documentation that exists but isn't perfectly formatted

Configuration styles that work but aren't your preference

Optimization Opportunities:

Performance improvements with minimal business impact

Cost reductions that aren't substantial

Tool upgrades that add features you don't really need

Criteria: These bother you aesthetically but aren't causing actual problems. Fix them only if you have free cycles (you won't) or if you're already touching that area for other reasons.

Tier 4: Leave Alone (Not Actually Problems)

"Different Than I'd Do It":

Design choices that work fine, but aren't your preferred approach

Technologies you're less familiar with, but the team knows well

Patterns that violate your assumptions but serve valid purposes

Low-Impact Legacy:

Old systems that work and nobody touches

Deprecated approaches that are isolated and stable

"Weird" configurations with historical reasons

Team Preferences:

Tools the team likes but you're less enthusiastic about

Workflows that differ from your experience but function well

Standards that are arbitrary but consistently applied

Criteria: No business impact. No technical impact. Just different than your preference. Let it go.

Distinguishing between actual technical debt and personal preferences is something I explored in Technical Debt: What Engineers Wish Managers Understood - not everything that feels wrong is actually wrong.

The Political Minefield: How to Actually Make Changes

Knowing what to fix is one thing. Successfully fixing it without destroying relationships or credibility is another.

The Credibility Problem

The Reality:

You're new, and you haven't proven yourself yet. You're inheriting systems built by people who might still work here.

What People Are Thinking:

"Who is this person coming in and immediately wanting to change everything we built?"

"Do they even understand why we did it this way?"

"Are they going to break things and blame us?"

"Are they trying to make a name for themselves by tearing down our work?"

Your Credibility Bank Account:

You start at zero. Every successful change is a deposit. Every failed change or broken relationship is a withdrawal.

You need deposits before you can make withdrawals.

Phase 1: Build Credibility Before Making Changes (Months 1-3)

What to Focus On:

Quick Wins That Nobody Disagrees With:

Fix things that are obviously broken and low-risk:

Obvious security gaps with clear fixes

Small automation improvements that save time

Documentation that's clearly missing

Tools that don't work, and everyone complains about

The Example:

I automated a report that someone was manually generating weekly and saved them 3 hours per week. Low risk, high appreciation. Quick credibility deposit.

Demonstrate Competence:

Show you understand the environment:

Successfully handle incidents

Make good technical decisions in real-time

Understand constraints and trade-offs

Contribute to problem-solving without taking over

Build Relationships:

With your team, with peers, with stakeholders:

Listen more than you talk

Ask questions with genuine curiosity

Acknowledge the good work that was done before you arrived

Demonstrate respect for institutional knowledge

The Investment:

This feels slow. You want to make big changes NOW. But you're building the political capital you'll need to make those changes successfully.

Phase 2: Propose Bigger Changes (Months 3-6)

Once You Have Some Credibility:

Frame Changes as Improvements, Not Criticisms:

Bad: "This design is wrong, and we need to redo it."

Good: "The current design has served us well. As we've grown, we're hitting some limitations. I'd like to propose an evolution that builds on what we have while addressing [specific business need]."

Acknowledge What Works:

Bad: "Everything about this architecture is problematic."

Good: "The core architecture has been solid. There are a few specific areas - [X] and [Y] - where I think we could improve reliability. The rest is working well."

Involve the People Who Built It:

Don't announce changes. Propose them and seek input:

"I've been thinking about [area]. Here's what I'm seeing as challenges. What's your perspective? What am I missing?"

If the original architect is still around:

"I know you designed this for good reasons. I'm trying to understand the constraints you were working with. Can you walk me through your thinking?"

Then later: "Based on what you've told me, I think we could address [issue] by [proposal]. What do you think?"

Make Them Part of the Solution:

People resist changes done TO them. They support changes they helped create.

Present Data, Not Opinions:

Bad: "I think we should change this."

Good: "We've had 5 incidents in the last quarter related to [issue]. Here's the data. Here's a proposal to address it. Here's the expected impact."

Data is less arguable than opinions.

Start with Pilot Programs:

Rather than: "We're changing everything to [new approach]."

Try: "Let's pilot [new approach] in [limited scope]. If it works, we'll expand it. If it doesn't, we'll adjust or abandon it."

Lower risk. Lower resistance. Easier to sell.

Phase 3: Larger Transformations (6+ Months)

Once You've Built Significant Credibility:

You've Successfully Delivered:

Multiple small improvements that worked

At least one medium-sized change that had a measurable impact

Demonstrated that you understand the environment and constraints

Now You Have Standing For:

Larger architectural changes

Multi-quarter transformation projects

Challenging organizational norms

Budget requests for significant infrastructure investment

But Even Now:

You still need to build consensus, involve stakeholders, and manage change carefully. You just have more credibility to spend on it.

Navigating Specific Political Scenarios

Let me get specific about situations you'll face:

Scenario 1: The Person Who Built It Still Works Here

The Situation:

You're inheriting infrastructure from someone who got promoted, moved to another team, or is still on your team.

The Trap:

Criticizing their work, even implicitly, damages the relationship and creates resistance.

The Approach:

Start with appreciation: "You built a solid foundation here. I'm learning a lot from understanding your design decisions."

Ask questions before proposing changes: "I'm looking at [area] and trying to understand the design. What were you optimizing for when you made this decision?"

When proposing changes: "Based on how our needs have evolved, I'm thinking about adjusting [area]. I wanted to get your input first since you designed this originally."

Frame changes as evolution, not replacement: "Building on what you created, I think we could address [new requirement] by [change]."

The Reality:

You're managing their ego and their sense of ownership. Done right, they become your ally in making changes. Done wrong, they become a source of resistance.

Scenario 2: "We Tried That Before, and It Failed"

The Situation:

You propose a change. Someone says "We tried that three years ago. It didn't work."

The Trap:

Dismissing this as resistance to change. Often, there's valuable context in past failures.

The Approach:

"I didn't know that. Can you tell me what happened? What made it not work?"

Listen. Really listen.

Then: "Based on what you're telling me, it sounds like [specific issue] was the problem. Here's how I think we could address that this time: [proposal]. What do you think?"

Why This Works:

You're acknowledging their experience, and you're learning from past failures. You're showing this isn't naive repetition.

Sometimes You'll Learn:

The reason it failed is still valid. The change actually won't work. They just saved you from a mistake.

Scenario 3: Your Team Disagrees With Your Assessment

The Situation:

You think something needs to change. Your senior engineers think it's fine as-is.

The Trap:

Pulling rank. "I'm the manager, we're doing it my way."

The Approach:

"I'm seeing [issue] as a problem because [reasoning]. You're saying it's not an issue. Help me understand what I'm missing."

Then:

Either you learn context that changes your mind, or you gather better data to make your case.

If you still disagree:

"I hear your perspective. I'm still concerned about [specific issue]. Let's try [small pilot] and evaluate the results together. If it doesn't address the problem or creates new issues, we'll reconsider."

The Reality:

Sometimes you're right, and they're wrong. Sometimes they're right, and you're wrong. Sometimes it's genuinely debatable.

Testing beats arguing.

Managing situations where your team disagrees with your technical decisions is part of leadership, something I touched on in 5 Things I Wish I Knew Before Becoming a Manager - your authority doesn't make you right.

Scenario 4: Leadership Wants Big Changes Immediately

The Situation:

Leadership hired you to "fix" things. They want to see quick, dramatic improvements.

The Trap:

Making big changes before you understand the environment. Breaking things. Alienating your team.

The Approach:

Set realistic expectations upfront:

"I'm seeing several areas where we can improve. Making these changes safely requires understanding the current environment thoroughly. Here's my 90-day plan:

Days 1-30: Assessment and quick wins on obvious issues.

Days 30-60: Detailed planning for bigger changes.

Days 60-90: Begin implementing larger improvements

This ensures we make changes that stick and don't create new problems."

Why This Works:

You're showing you have a plan and you're demonstrating thoughtfulness, not recklessness. You're managing expectations.

The Quick Wins:

Identify a few low-risk, high-visibility improvements you can deliver in the first 30 days. This buys you credibility and patience for the bigger changes.

What I Wish I'd Done Differently

Let me be honest about my mistakes:

Mistake 1: Judging Too Quickly

What I Did:

Looked at the network architecture in week two and decided it was poorly designed. Started planning a redesign.

What I Should Have Done:

Spent 60-90 days really understanding WHY it was designed that way before concluding it was wrong.

What I Learned:

About half the things I initially thought were "wrong" turned out to be "right for reasons I didn't understand yet."

Mistake 2: Changing Things Without Building Consensus

What I Did:

Implemented a configuration standard change that I thought was obviously better. Didn't really consult the team.

What Happened:

The change broke an edge case I didn't know about. The team resented not being consulted. Lost credibility.

What I Should Have Done:

"Hey team, I'm thinking about changing [thing] to address [issue]. What am I not seeing? What could go wrong?"

Mistake 3: Criticizing Previous Decisions

What I Did:

In a meeting, I said something like "the previous design wasn't ideal" in front of people who built it.

What Happened:

Created defensiveness. Damaged relationships. Made future changes harder.

What I Should Have Done:

"The previous design served its purpose well. As our needs have evolved, I think we can make some improvements."

Same message, no criticism.

Mistake 4: Not Documenting My Reasoning

What I Did:

Made changes based on what seemed obviously right. Didn't document why.

What Happened:

Six months later, someone questioned the changes. I couldn't clearly explain the reasoning. Made it look arbitrary.

What I Should Have Done:

Document every significant change: what problem it solves, why this approach, what alternatives were considered, and what success looks like.

Mistake 5: Trying to Fix Too Much Too Fast

What I Did:

Identified 20 things that needed improvement. Tried to tackle 10 of them simultaneously in months 2-3.

What Happened:

Change fatigue. Quality suffered. Some changes failed. Lost focus.

What I Should Have Done:

Pick 2-3 high-impact changes. Do them well. Build credibility. Then tackle the next batch.

The Bottom Line: Patience Is a Strategy

Here's what I'm learning six months in:

The network you inherited probably isn't as broken as you initially think. Give yourself time to understand the context before judging.

Your job isn't to prove you're smarter than the people who came before you. Your job is to make things better going forward.

Credibility takes time to build and seconds to destroy. Every change is a test of your judgment. Make sure you pass more tests than you fail.

Political capital is real. You need it to make changes. You build it through successful small changes, not ambitious failures.

Involving people in changes is slower but more successful. Consensus-building feels inefficient. It's actually the fastest path to lasting change.

Not everything that bothers you needs to be fixed. Save your energy and political capital for things that actually matter.

The people who built this infrastructure aren't idiots. They made decisions based on constraints and context you don't fully understand yet. Seek to understand before you criticize.

Sometimes "we've always done it this way" has good reasons behind it. Sometimes it doesn't. Your job is figuring out which is which.

You will make mistakes. You'll change things that should have been left alone. You'll leave things alone that should have been changed. Learn from them and do better next time.

The long game matters more than quick wins. Building a reputation as someone who makes thoughtful changes that work beats being someone who moves fast and breaks things.

The Framework I'm Using Now

Month 1: Assess and Quick Wins

Understand what exists and why

Fix obvious problems everyone agrees on

Build relationships

Document findings

Month 2-3: Plan and Build Consensus

Identify real problems vs. preferences

Propose changes and gather input

Pilot small improvements

Demonstrate competence

Month 4-6: Implement Bigger Changes

Execute well-planned improvements

Measure and communicate results

Adjust based on feedback

Build credibility for the next phase

Month 6+: Larger Transformations

Tackle architectural changes

Multi-quarter projects

Challenge organizational norms

Drive strategic improvements

The Key:

Each phase builds on the previous one. Skip steps, and you'll fail. Rush the process, and you'll break things or relationships.

Slow is smooth. Smooth is fast.

Related Posts

📧 Navigating a new role or inherited infrastructure? Subscribe to my monthly newsletter for practical perspectives on technical leadership, making changes that stick, and learning from the mistakes I'm making in real-time. First Tuesday of every month. Sign up below!

Have you inherited someone else's network? What did you change? What did you leave alone? What would you do differently? Share your experiences in the comments or connect with me on LinkedIn - we're all learning this together.